Fast Fashion’s Ugly Price Tag

November 26, 2019

Take a moment to look down and ask yourself, what am I wearing today? Chances are you’re literally wearing a product of “fast fashion”: a term used to describe the readily available, inexpensive, throwaway fashion of today. This rapid method of apparel manufacturing sacrifices both material efficacy and sustainability in order to capitalize on the fashion industry’s heavy reliance on the latest style trends. By pumping out these new, desirable styles weekly, popular brands such as Zara, TopShop, Forever 21, Zaful, Boohoo, and Fashion Nova have a towering supply of stock at all times. This, in turn, has led consumers to adopt a dangerous, linear fashion cycle: buying, wearing, and quickly discarding massive amounts of clothes.

Take a moment to look down and ask yourself, what am I wearing today? Chances are you’re literally wearing a product of “fast fashion”: a term used to describe the readily available, inexpensive, throwaway fashion of today. This rapid method of apparel manufacturing sacrifices both material efficacy and sustainability in order to capitalize on the fashion industry’s heavy reliance on the latest style trends. By pumping out these new, desirable styles weekly, popular brands such as Zara, TopShop, Forever 21, Zaful, Boohoo, and Fashion Nova have a towering supply of stock at all times. This, in turn, has led consumers to adopt a dangerous, linear fashion cycle: buying, wearing, and quickly discarding massive amounts of clothes.

According to the World Resources Institute, “Approximately 85% of the clothing Americans consume, nearly 3.8 billion pounds annually, is sent to landfills as solid waste, amounting to nearly 80 pounds per American per year… that means that the annual value of clothing discarded prematurely is more than $400 billion.” That’s not all, though. In the book Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, author Elizabeth Cline claims that “more than 60% of fabric fibers are now synthetics, derived from fossil fuels,” meaning that when this clothing inevitably ends up in a landfill, “…it will not decay…nor will the synthetic microfibers that end up in the sea, freshwater and elsewhere, including the deepest parts of the oceans and the highest glacier peaks.” But does the landfilling and ocean polluting of non-synthetic clothing matter? Yes, because it contributes to global emission of methane, a potent heat-trapping gas. In other words? We are killing our planet by supporting the fast-fashion industry.

But why are these numbers and facts so staggering? Fast fashion’s manipulative marketing takes advantage of everyone, from frugal mothers to teenagers with low budgets and even lower self-esteem, only desiring to fit in with their “stylish” peers. These brands further extend their influence over young people by sponsoring attractive models and other public figures on social media, who are followed by waves of these impressionable teenagers.

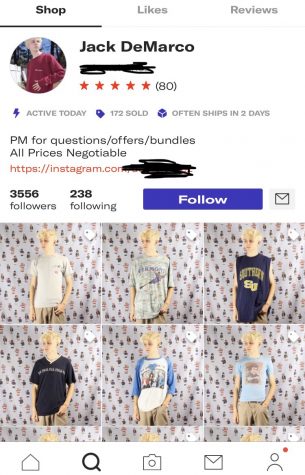

However, there are young people out there who don’t fall into this devious trap, such as Ipswich High School’s own Jack Demarco. Demarco has traded Saturday afternoons with his friends at the shopping mall for selling thrifted garments on online platforms such as Depop, Poshmark, and Ebay. “It’s a culture,” he says, “people like finding homes for old, pre-loved vintage clothes. It’s really cool to have the opportunity to do something like that.”

In the past three years, Demarco has sold over 400 articles of clothing across the United States. Clearly, has made enormous profits despite the 10% fee he is charged by these companies. This is evidence that people are definitely attracted to the appeal of reusing clothing. Other business models based on longevity, such as Rent the Runway, are the beginnings of an industry that supports reuse instead of rapid and irresponsible consumption. Just as Netflix reimagined traditional film rental services and Uber changed the transportation game, we are beginning to see options for consumers to lease clothes rather than buy and stash them in their closets. Jadzia Roberts, a loyal Rent the Runway consumer, gushes about the company’s appeal. “I love it, though I might use it a bit too often,” she admits, “I have an unlimited subscription for $136 a month. I wear beautiful, high-quality items and send them back once I’ve satisfied that itch for something new. I just think that it’s a great alternative to going out and buying a bunch of clothes that I’ll only wear once or twice, like for a wedding or Christmas party.” These companies also claim to recycle the boxes, plastic wrap, and plastic clothing hangers the clothing is shipped with, offsetting the pollution of the shipment process.

Ultimately, there really is no logical reason as to why we purchase brand new clothes every month: we only do so because we want to, because these fast fashion companies tell us we want to. We can combat fast fashion by following Demarco or Robert’s example, or we can support “slow-fashion” instead, clothing made with locally grown materials, often domestically manufactured or sourced on a relatively small scale.